Greg Nyquist |

Touring America's Northwest: Northwestern California

If we were to follow the usages propagated by the travel guides, Northern California would refer almost exclusively to San Francisco and the Bay Area, along with Yosemite, Lake Tahoe, Monterey, Carmel, and the Napa Valley. Yet all these places more properly belong — at least from a strictly geographical perspective — to central California. They are categorized under the Northern California heading merely to distinguish them more sharply from the great sprawling smog enshrouded über-metropolises of Southern California proper. By demarcating California in this fashion, short shrift is given to that part of the state that actually resides to the north. There is a reason for the slight.The northernmost section of California is so very different from the rest of the state — or at least from the common perceptions of the rest of the state — that it can hardly be considered, in any meaningful sense of the word, as being part of California. The nations most populous state is, above all, a region of vast, sprawling population-engorged suburbias. Miles upon miles of housing developments, spread across the flatlands and reaching up into the hills and canyons. Everywhere you turn, you find houses and strip malls and freeways choked with automobiles. Northern California is very different from the rest of the state. For one thing, it is much less crowded, with a rural flavor present over much of it. North of Lake Tahoe, there is only one city with a population over 100,000 (Redding, with a population of 104,295). Indeed, there are only a handful of counties (two, in fact, Humboldt and Shasta) that reach six figures in the census. The northernmost part of California, like the southeastern portion, is only marginally populous and consequently takes on a different character from the rest of the state.

Since fewer people live in Northern California proper, the travel books tend to regard it as much less interesting and much less significant. To be sure, they may mention, in passing, a few points of interest for the intrepid traveler: the towering redwoods along the northcoast; the immensity of Mount Shasta; Lassen Volcanic National Park; and some of the larger recreational lakes in the area, such as Lake Shasta and Lake Oroville. But little if anything is said about the Klamath River, the state's second largest river; or about the Coastal Ranges, or Klamath or Warner Mountains; and nothing at all is said about the many wilderness areas that enclose hundreds of miles of deer and squirrel infested woods and canyons framed by lofty granite ridges.

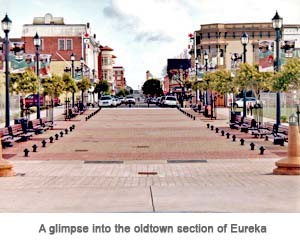

My tour of Northwest America begins on the northcoast of California, in the modest seaport berg of Eureka. Only twenty years ago, Eureka was rated one of the three or four best places to live in the United States, and the best small art city in America. It features one of the most temperate climates to be found anywhere. The average high in the summer (63°) is only eight degrees higher than the average high in the winter (55°). This does not mean that winters are hardly distinguishable from summers on the northcoast. Eureka receives as much annual precipitation as Seattle: 37 inches in all, the lion's share of which falls between November and April. Summers in Eureka are cool and dry; winters, chilly and wet. But hot weather or cold weather rarely visits the wind swept coasts of Northern California.

According to the census, the population of Eureka hardly exceeds 27,000; but this figure is misleading, because Eureka proper spills out into several neighboring communities, creating a single, unified metropolitan area with a population exceeding 50,000. If you throw in the two cities to the north,, Arcata and McKinleyville, along with the city just to the south, Fortuna, you have a population approaching 100,000 enclosed within a thirty mile stretch. Yet this 100,000 reside in one of the more remote areas of the United States. By remote, I mean primarily: hard to access. All the roads leading into the are — at least in large stretches — winding two-lane affairs. The major coast route connecting Eureka to San Francisco, Highway 101, winds its tedious way through the valleys and river canyons of California's coastal ranges. To the east is California's widest mountain range, the expansive Klamath Mountains: nearly one hundred miles of crisscrossing ridges and steep, tree and chaparral infested ravines. To the north, more coastal mountains, dotted with immense trees. During a particularly bad storm it is not unusual for some of the roads, many of them perched on the edge of steep river carved ravines, to become impassable. Bits of the road may crumble into the raging river below. Or the mountain above will spill out onto the road. Merely to keep these roads open requires an immense expense. Some years ago, a railroad connected Eureka to the Bay Area. In the nineties, however, a severe winter storm washed away several critical sections of the railroad, rendering it unusable.

In common with many another semi-isolated rural community, California's northcoast has been hit hard by growing environmental tensions.A region that once thrived on logging and fishing now depends heavily on state jobs, state subsidies, and public assistance. I cannot vouch for the absolute accuracy of the statistic, but it is claimed that as many as two-fifths of the population of Eureka receive, either directly or indirectly, most of their income from the government. Some work for the state, while others merely receive benefits of some sort or another — whether social security, disability, food stamps, or other forms of the dole, it hardly matters.

I cannot vouch for the absolute accuracy of the statistic, but it is claimed that as many as two-fifths of the population of Eureka receive, either directly or indirectly, most of their income from the government. Some work for the state, while others merely receive benefits of some sort or another — whether social security, disability, food stamps, or other forms of the dole, it hardly matters.

Dependence on the state has provided a leftward tilt to local politics, a leaning that has been egregiously intensified by the dominance of Humboldt State University within the political and social culture of the Arcata, Eureka's sister city to the north. American universities present a baneful, poisonous influence wherever they are situated. But at least populous communities are able to absorb and dilute, to a certain extent, whatever toxins are injected into the local community. Not so, however, with a small town, which is soon overwhelmed and, in a sense, taken over by the local university. Arcata represents an unedifying example of this ghastly process. It may be the most leftist city in America, with a city council dominated by the Green Party. The mayor of Arcata, a Green Party twenty-something with the Dickensian name Harmony Groves, presents an enigmatic figure to the student of leftist politics, manifesting, as she has in her brief political career, an odd mixture of left-wing idealist bumpersticker mentality on the one hand and clumsy machiavellian pragmatism on the other. For some odd reason or another which no one has been able to explain, Groves appears to be opposed to one of the Left's most favorite panaceas: police review, which grants local busybodies and other troublemakers the right to second guess the conduct of any police officer. As a progressive of good standing, Groves has not, of course, actually come out against police review. But she has never publicly supported the measure and, even more to the point, managed to recuse herself from voting for it on the flimsiest of grounds. "It is in the public's interest for an elected official to step down when there is a conflict of interest," she later wrote in an attempt to justify her recusal. "The individuals who showed up to speak to the council regarding a Police Review Board were clients of my current employer." In other words, somebody who didn't like police review complained about it to the city council, and because this person was a client of Groves' employer, she recused herself from taking a vote on the measure, thus preventing it from passing. Why Groves, who is absurdly progressive on nearly every other issue, finds herself unable to support police review, a measure fervently supported by her own Green Party, is anyone's guess.

Serving as a piquant counterpoise to Arcata's cadre of radical leftists is the northcoast's exasperated and volatile redneck contingent. Although outnumbered, they are not in the least outgunned. Word is, they are armed to the gills and seething with indignation over what Arcatan leftists — along with their like-minded allies scattered throughout the rest of the county, such as the local District Attorney, the quixotically incompetent Paul Gallegos — are doing to the community. Fears of right-wing vigilantism form one of the undercurrents of the political culture. "From reports I heard from activists that talked to police today," griped one clearly frightened and almost certainly unhinged leftist, "it seems that the City of Arcata is depending on vigilantes to prevent free speech and protest in Arcata. A culture of support for vigilantism seems to flourish in Humboldt County, thanks to the silence of the community and clergy. This is certainly what must have happened in Germany that allowed Hitler to come to power." The rednecks enjoy stirring up this sort of paranoia by making all sorts wild threats about turning Arcata into a leftist hunting preserve. Wild threats for the nonce, but maybe not for very long. For there is real frustration, real anger in the redneck community, building up like the pressure in a volcano, until the day when it can be contained no longer and must erupt into an orgy of bloodletting. After all, only societal inhibitions built up through generations of authoritarianism prevent such seemingly idle threats from flaming into sanguinary deeds — inhibitions, moreover, which the left itself, with its fierce though not very discriminating or intelligent antinomianism, seems bent on undermining. Hence we find the radical left unwittingly working for its own destruction — as always!

Given all the political, social, and economic ills that trouble the northcoast, why would anyone want to live there? Well, there are considerations that have to be weighed in the balance on the other side, the chief among them being the region's lush verdurous beauty, with pristine groves of old growth redwoods on the on hand, and rocky windswept or fog strewn seascapes on the other.  A pine or fir forest is a lovely thing; but all such forests, regardless of the trees that make up their ranks, pale into insignificance when compared with a forest of mighty redwoods. Ordinary trees, no matter their size or scope, all appear as mere weeds, scrawny and lilliputian, beside a redwood. Now imagine not just one or two such massive trees, but acres of the giant sky ascending behemoths, reaching to well over 300 feet in height and spreading a green canopy of cathedral-like dimensions over a forest floor carpeted in ferns and blooming rhododendrons. The northocoast features dozens of groves well surpassing this description.

A pine or fir forest is a lovely thing; but all such forests, regardless of the trees that make up their ranks, pale into insignificance when compared with a forest of mighty redwoods. Ordinary trees, no matter their size or scope, all appear as mere weeds, scrawny and lilliputian, beside a redwood. Now imagine not just one or two such massive trees, but acres of the giant sky ascending behemoths, reaching to well over 300 feet in height and spreading a green canopy of cathedral-like dimensions over a forest floor carpeted in ferns and blooming rhododendrons. The northocoast features dozens of groves well surpassing this description.

The major mountain range in the northwestern part of California is the Klamath Mountains, a large complex of peaks and gorges and rivers and lakes. If all you ever saw of the Klamaths is what you gaped at from you car window as you navigated the curving, twisting Highway 299, you would not likely be very impressed or come away with a particularly high opinion of the range. Oh, it's scenic enough, this drive carved along the steep ridges carved by the Trinity River. But nothing you see will compare favorably to the much richer vistas provided by the Sierra Neveda, the Northern Cascades, or the Canadian Rockies. Rather ordinary, even undistinguished mountain scenery: better, perhaps, than foothills or plains; but nothing so impressive as to warrant a national park or wilderness preserve. Sections of this road lapse from merely pretty into a sort of raw plainness bordering on downright ugliness. Take the river area around Junction City, a little slip of a town with a gasoline station and a handful of rickety shack-like structures perched along the roadside, as a typical example. The river bed that runs by the town stretches very wide — much too wide to include normal flows of water. So all you see for a great distance is a dry, sandy, washed out flood plain, strewn with rocks and stones of various sizes, and surrounded by steep grass, tree, and chaparral covered mountains. In the summer, a hot, miserable little berg of a town; in the winter, even worse — chilly and wet, beset with brisk winds and bitter morning frosts. Not a very pleasant place, is this Junction City. Beset by fire dangers in the summer, by endless rain and occasional snow in the winter.

Sections of this road lapse from merely pretty into a sort of raw plainness bordering on downright ugliness. Take the river area around Junction City, a little slip of a town with a gasoline station and a handful of rickety shack-like structures perched along the roadside, as a typical example. The river bed that runs by the town stretches very wide — much too wide to include normal flows of water. So all you see for a great distance is a dry, sandy, washed out flood plain, strewn with rocks and stones of various sizes, and surrounded by steep grass, tree, and chaparral covered mountains. In the summer, a hot, miserable little berg of a town; in the winter, even worse — chilly and wet, beset with brisk winds and bitter morning frosts. Not a very pleasant place, is this Junction City. Beset by fire dangers in the summer, by endless rain and occasional snow in the winter.

How, may we ask, does any sane person find it within his heart to live in so obscure and God-forsaken a hamlet as this? What do the locals do with themselves, sweating in the summers, shivering in the winters? Well, if appearances can be our guide, we must conclude, from the look of the some the local buildings, that at least a few of the town's residents have given bent to an architectural fancy of a semi-civilized variety. Driving up Canyon Creek Road one finds, for one's edification and amusement, some of the most imaginative examples of redneck architecture to be found anywhere in the United States. Particularly noteworthy, in this respect, is the enterprising yahoo who has seen fit to extend the grandeur of his decrepit, barn-like shack of a house by pasting on the addition of a half-rusted house trailer. There are few things more inspiring in a simian, missing-link kind of way than the curious spectacle of a house trailer virtually growing out of the side of a barn.

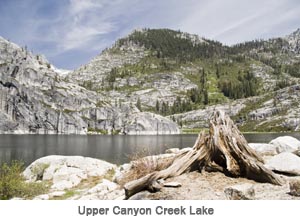

Although the impression given by Junction City and its immediate environs is hardly one that speaks strongly for the aesthetic qualities of the Klamath Mountains, it would be an immense folly to judge the entire mountain range on this one spot. For not more than twenty miles north of this eye sore of a hamlet resides two of the most gorgeous mountain lakes that ever graced a picturesque mountain canyon. If you drive up Canyon Creek Road thirteen miles to the very end, you will find a parking lot, often overflowing with cars on summer weekends. Here commences the trailhead into Canyon Creek, the so-called Yosemite of the Trinity Alps Wilderness, which contains some of the most scenic granite mountain splendor this side of the Sierras. If you get yourself out of your car and begin hoofing your way up the trail, soon you will find yourself within a steep forested canyon, framed by high granite walls, with lush meadows, gurgling streams and rivulets, roaring waterfalls, rugged snow-capped granite peaks, and shimmering blue lakes, mirroring their granite enclosures in the early morning stillness. One of the most beautiful places on earth, is Canyon Creek. And yet for those poor benighted souls who stick to Highway 299 and adjoining roads, they would have no idea that any such mountain wonderland exists just ten miles over the unprepossesing ridge to their left. That is the great secret of the Klamath Mountains. The scenic parts are hidden deep within the innermost bowls of the range, away from any of the major roads or easily accessed lookout points. Deep in the interior of these mountains lie immense wilderness areas: the Trinity Alps Wilderness, the Marble Mountains Wilderness, the Siskiyou Wilderness, the Red Buttes Wilderness, the Castle Crags Wilderness, and the Yolla Bolly Middle Eel Wilderness. These wilderness areas, where no cars or motorized vehicles of any description can enter, contain the lion's share of the region's splendours, with more than one hundred lakes framed by peaks of burnished granite, marble, and diorite.

And yet for those poor benighted souls who stick to Highway 299 and adjoining roads, they would have no idea that any such mountain wonderland exists just ten miles over the unprepossesing ridge to their left. That is the great secret of the Klamath Mountains. The scenic parts are hidden deep within the innermost bowls of the range, away from any of the major roads or easily accessed lookout points. Deep in the interior of these mountains lie immense wilderness areas: the Trinity Alps Wilderness, the Marble Mountains Wilderness, the Siskiyou Wilderness, the Red Buttes Wilderness, the Castle Crags Wilderness, and the Yolla Bolly Middle Eel Wilderness. These wilderness areas, where no cars or motorized vehicles of any description can enter, contain the lion's share of the region's splendours, with more than one hundred lakes framed by peaks of burnished granite, marble, and diorite.

Seven miles east of Junction City, nestled in a pleasant mountain valley, lies Weaverville, the largest metropolis in these parts, with a population of 3,554. Weaverville serves as the county seat for Trinity County, one of the more remote counties in California — so remote, in fact, that not a single traffic light resides within its borders. Merely stop signs and free access.

From Weaverville, traveling east, Highway 299 ascends to Buckhorn Summit, which, at 3,212 feet in elevation, represents the highest point of the highway between Eureka and Redding. Past the summit is where 299 begins to earn its props as a mountain road, with several miles of hairpin curves, one on top of the other — really one of the better weave until you heave roads in these parts. Slowly and painfully, the curves abate as the road straightens out and whips by Whiskeytown Lake.

Slowly and painfully, the curves abate as the road straightens out and whips by Whiskeytown Lake.

Once past Whiskeytown Lake, the Sacramento Valley, often shrouded, particularly in the summer months, in bright sun-scorched haze, opens before us. Not much of the scenic to be found in this valley, once we are cleared of the surrounding mountains. Only the sprawling houses and strip malls of Redding and its adjoining suburbs, surrounded by nondescript farm and ranch land. And the heat, the endless, blistering heat: especially in the Summer, when the thermometer can easily find itself well over 100°. In other words, just plain nasty — a climate near akin to hell itself!

Passing through Redding from east to west, or west to east, is always a painful, tedious business. One must navigate through a maze of traffic choked streets, making right turn here, a left turn there, and another left turn just around the corner. But once safely back on Highway 44, eastbound, the impatient tourist can hasten himself out of Redding very speedily. In a few miles, the highway sheds a couple of lanes and courses its way along miles of endless billowy grass strewn hills, yellowing in the sweltering sun. On the horizon ahead looms Mount Lassen. We are entering Northeastern California.

To read about northeastern California, go here.

Greg Nyquist is the webmaster for jrnyquist.com. He can be reached at machiavel@mac.com.