Greg Nyquist |

Touring America's Northwest: Northeastern California

Editor's Note: This article is second in a series of travel sketches from America's northwest, including northern California, Nevada, Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, Washington, and Oregon. You can read the first article in the series, on northwestern California, by going here.

The southern Cascades have a trick of sneaking up on you. The terrain gradually and unobtrusively sneaks up toward them. You hardly notice the rise in elevation. One moment, you are passing miles of grassland; the next moment, you find yourself ensconced in an immense forest.

Much of Northern California lies on a high plateau liberally sprinkled with mountains ranges of varying in scope and size. These miscellaneous mountains constitute the southern tip of the Cascade Mountain Range, the largest such range west of the Rockies. Like the Rockies, the Cascades generally become more interesting the farther north you travel among them, with North Cascades National Park, in Washington, being the crown jewel of the range. But there are points of interest in the southern part of the range as well, the most important being Lassen Volcanic National Park, which is, after Mount St. Helens, the most volatile and active part of the range. Lassen last suffered a major eruption in 1915.

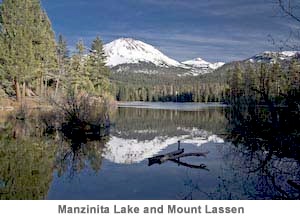

Today, Lassen has three main attractions for the casual tourist. First, there is Manzinita Lake which, on a windless evening, proves a perfect mirror to Mount Lassen and the adjoining mountain ranges.  Next, there is Mount Lassen itself, the summit of which is easily gained by a short though steep trail. And finally, there is Bumpass Hell, a miscellaneous collection of steaming vents and boiling mudpots. Lassen is somewhat reminiscent of Yellowstone, except on a much smaller scale, with no geysers, no Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, and no bison. Just the usual forests, meadows, lakes, with the occasional mountain range rising from the volcanic plain. Both parks rest on potentially explosive thermal areas: places where hell itself threatens to burst forth from the earth's crest.

Next, there is Mount Lassen itself, the summit of which is easily gained by a short though steep trail. And finally, there is Bumpass Hell, a miscellaneous collection of steaming vents and boiling mudpots. Lassen is somewhat reminiscent of Yellowstone, except on a much smaller scale, with no geysers, no Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, and no bison. Just the usual forests, meadows, lakes, with the occasional mountain range rising from the volcanic plain. Both parks rest on potentially explosive thermal areas: places where hell itself threatens to burst forth from the earth's crest.

For those in a hurry to get from Redding to Reno, Lassen is an obstacle to be circumvented. Highway 44 swings to the north of the park and leas off toward Susanville, the county seat for Lassen County and, with a population of more than 13,000, the largest city in northeastern California. Of Susanville itself, I remember little if anything beyond the fact that there is nothing memorable in it nor anything worth remembering about it.

Five miles south of Susanville, the intrepid traveller connects to Highway 395, one of the great roads of the West, beginning, as it valiantly does, as little more than an offshoot from Highway 15, thirty miles north of San Bernardino, and carefulling edging its way along the backside of the Sierra Nevada and the southern Cascades, before taking off into the vast deserts and mountains of eastern Oregon, only to find its ultimate terminus in Pendelton, Oregon. It is doubtful that very many people have driven from one end of Highway 395 to the other — for who in their right mind would ever wish to visit Pendelton?

Highway 395 has, beyond its ultimate destination, an additional disadvantage — namely, that of spending a good portion of its length on the eastern side of immense mountain ranges. In the western United States, all the big winter storms come in from the Pacific Ocean. As these storms approach the western slopes of the Cascades and the Sierras, the upward pressure of the air helps produce huge amounts of snow.The opposite effect is in play as the air rushes down the eastward slope, where the downward flow of the storm creates warm, dry air. This accounts for what is known as a mountain's "rain shadow," where much less precipitation falls than on the other side of the divide.

The great deserts of the United States all fall on the rain shadow side of lofty mountain ranges. Directly behind the northern Sierras you find something very close to a desert, as you travel along Highway 395: a semi-arid plateau made up of billowing hills covered in grass turned golden brown by the relentless summer sun. In all honesty, the terrain behind this section of the Sierras is very similar to the terrain to be found throughout much of the western U.S., particularly on the eastern side of mountain ranges. Those who have driven between Los Angeles and San Francisco along Interstate 5 will have an idea of the look of the place, for it is very similar to what is to be found on the western side of the San Joaquin Valley, in the rain shadow of the coastal ranges. A landscape of rounded hills for miles without end; mildly picturesque, particularly in evening or early morning light, without ever approaching the spectacular: that about sums up this section of northern California. Why anyone would want to live in such a place constitutes one of the great mysteries of life. But as a matter of fact, not many people do live in this region east of the northern Sierras. Not, at least, until one crosses the border into Nevada and finds oneself on the outskirts of the oddly burgeoning metropolis of Reno.

To read the next article in this series, about Nevada, go here.

Greg Nyquist is the webmaster for jrnyquist.com. He can be reached at machiavel@mac.com.